DOYLE, Rich. « Hyperbolic : Divining Ayahuasca », Discourse, vol. 27, no1, 2001, p. 6–33. ITOH, Teiji. The Gardens of Japan, Tokyo, Kodansha, 1998, 244 p.

LINGIS, Alphonso. Body Transformations: Evolutions and Atavisms in Culture, Routlege, New York et Londres, 2005, 160 p.

MORTON, Tim. Realist Magic, Objects, Ontology, Causality, Ann Arbor, Open Humanities Press, 2013, 228 p.

NAKAGAWARA, Camelia. « The Japanese garden for the mind : The ‘Bliss’ of Paradise Transcended », Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs, vol. 4, no2, 2004, p. 83-102

WATTS, Allan. Out of Your Mind : Essential Listening from the Alan Watts Audio Archives, Sounds True Audio, 2004.

_____________________________

Alfonso Lingis: “Things are relays of the voice of the spirit.”

Dans un article à propos de ses expériences avec l’Ayahuasca, Rich Doyle relate un moment où il a senti que l’esprit de la plante l’invitait à lui poser une question :

« Without thinking, I asked it what the Universe was. The universe is a way of tricking itself. Next question. »

« This trickster ontology might remind us that the cosmos is capable of transforming itself in suddenly novel ways, forgetting its own premises... »

Leyla me parlait souvent des tricksters, ces esprits archétypaux, joueurs de tours inquiétants. Ces entités peuvent être naturelles ou surnaturelles : animaux dotés de pouvoirs ou d’une intelligence inusités, phénomènes météorologiques, maîtres du camouflage et autres étranges forces invisibles qui vivent parmi nous.

Elle m’a appris qui étaient les yokai dans le folklore japonais, ces êtres aux limites du langage et à travers lesquels s’expriment diverses énergies. Je lui confiais que, devant son travail, je me retrouvais comme un nourrisson dans son berceau. Ces formes espiègles et malicieuses, qui sourient et nous fixent, ont quelque chose de troublant. En psychanalyse, on parlerait de l’esprit dans sa forme primitive, ou d’un esprit « indifférencié », qui ne saurait distinguer sa dynamique interne de la vie au-delà du soi. Cet espace peut avoir quelque chose d’intimidant. Certains s’y sentent un brin paranoïaques. D’autres, curieux de comprendre les influences subtiles qu’y exercent ces étranges assemblages de formes, y découvrent des intentions et des énergies qui dépassent leur entendement. Le monde, comme le disait Alan Watts, est plus frémissant que nous ne sommes prêts à l’admettre.

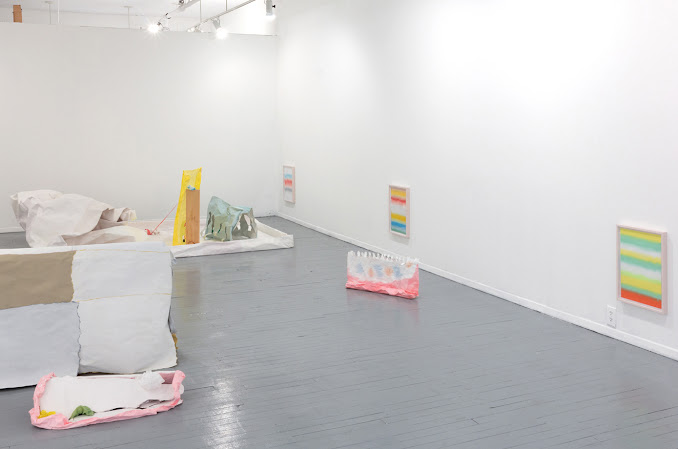

Leyla est une jardinière, collaborant à la création d’un paysage. Elle travaille avec des matériaux simples, à l’état brut : du papier, de la peinture. Et pourtant, ses formes naturelles et subtiles ne relèvent en rien de l’évidence. Les visages souriants, sa signature, sont à la fois l’expression de l’artiste et celle d’un geste qui la dépasse, comme autant de clins d’œil à un monde inconnu.

Selon Nakagawara, dans l’art traditionnel des jardins japonais, « le paysage, objet de contemplation en soi, véhicule toujours un sens. Il s’oppose au simple lieu, qui lui ne véhicule que la présence humaine ». Dans cette tradition, comme dans plusieurs autres, les pierres sont des êtres vivants, porteurs d’une signification qui dépasse les préoccupations humaines. Dans ces jardins, comme dans bien d’autres endroits sur terre, les pierres sont les marqueurs d’un lieu visité par les dieux. Leyla ne cherche pas la représentation d’entités particulières. Son travail ne s’applique ni à la mystification, ni

à la conjuration d’une quelconque illusion, préférant plutôt nous orienter vers le paysage et les êtres qui l’habitent. L’artiste nous apprend ainsi l’art du jardinage, attirant notre attention vers le sol, et ce qui se trouve entre les strates de la pensée magique.

Dans ce travail, les matériaux libèrent leur puissance évocatrice. Des formes vulnérables en mutation s’y appuient les unes aux autres, se sous-tendent et se soutiennent. La structure de l’ensemble est instable et les agencements qui en résultent paraissent pâles, délicats, chancelants. Certaines formes se montrent incomplètes : un côté manquant, une partie évidée. Par ces trous, ces ouvertures, l’invisible s’insère dans la trame de la structure telle une présence impalpable, un membre fantôme.

Tim Morton : « Every event in reality is a kind of inscription in which one object leaves its footprint in another one. »

Notre collaboration relève de la biodynamique et de la psychodynamique. Notre approche est transdisciplinaire. Ainsi, le travail d’une jardinière consiste à creuser et entretenir divers aspects de la matière, en y déterminant ce dont chacun a besoin pour croître et s’épanouir, les types de relations bénéfiques à la vie et le rôle que la mort doit parfois y jouer. Ce travail présente des similitudes avec celui de la thérapeute, bien que celle-ci s’occupe d’une toute autre matière. Dans les deux cas, beaucoup de temps et d’attention doivent être consacrés à réunir des conditions optimales. Ce n’est qu’en leur présence qu’on peut espérer voir éclore un petit quelque chose. La plupart des phénomènes reliés à ces deux domaines d’études sont à peine perceptibles, au début. À travers les pratiques et les paradigmes du soin, ceux qui exigent que l’on s’occupe de l’esprit d’une chose qui nous échappe et nous surprend, chacune de nous collabore avec des formes de vies matérielles et immatérielles. En ce sens, le travail de Leyla nous invite à revoir notre rôle au sein d’une plus vaste communauté d’êtres.

Texte de Katherine Kline (traduction)

-

DOYLE, Rich. « Hyperbolic : Divining Ayahuasca », Discourse, vol. 27, no1, 2001, p. 6–33. ITOH, Teiji. The Gardens of Japan, Tokyo, Kodansha, 1998, 244 p.

LINGIS, Alphonso. Body Transformations: Evolutions and Atavisms in Culture, Routlege, New York et Londres, 2005, 160 p.

MORTON, Tim. Realist Magic, Objects, Ontology, Causality, Ann Arbor, Open Humanities Press, 2013, 228 p.

NAKAGAWARA, Camelia. « The Japanese garden for the mind : The ‘Bliss’ of Paradise Transcended », Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs, vol. 4, no2, 2004, p. 83-102

WATTS, Allan. Out of Your Mind : Essential Listening from the Alan Watts Audio Archives, Sounds True Audio, 2004.